The 115th Congress of the United States has been in session less than a week, and many of our basic rights are already under attack.

The news about gutting the Office of Congressional Ethics, Russian interference in U.S. elections, and plans to push through unqualified Cabinet nominees is terrifying enough. But we also have to face the very real possibility that millions of people will lose access to basic health care, whether through the loss of the Affordable Care Act or through the planned defunding of Planned Parenthood.

Health care in America is broken, that is no secret. Health care for women varies dramatically based on what state you live in. Roe v. Wade has been under constant attack since it was decided in 1973, and Planned Parenthood’s providers have had to take dramatic measures to ensure their safety.

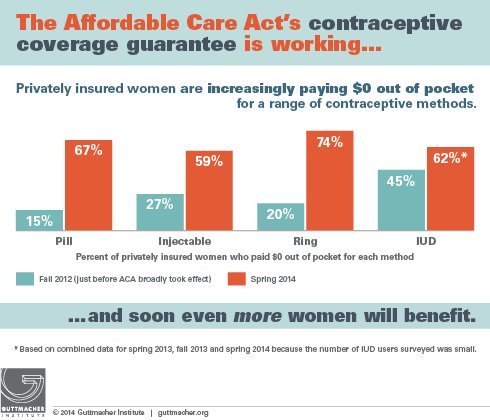

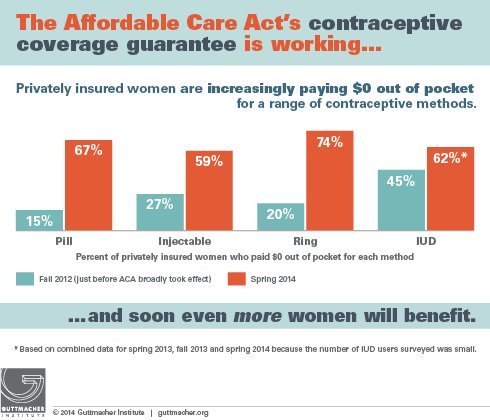

Coverage for men and women has varied dramatically through the years and among insurance carriers. The ACA brought about universal coverage of birth control for women, but insurance companies are not required to cover any type of male birth control. And, if you work for a religious institution, it’s possible that your insurance plan might be exempt from this mandate.

Despite all the loopholes and exceptions, the birth control mandate has been a hugely positive part of the ACA.

Now I’m going to get personal.

James and I are agreed that two children is the right number of children for our family. Our house has no more bedrooms, our cars have no more seats, our salaries can’t stretch any farther. Two is perfect for us.

Before our second was born, James decided that he would like to have a vasectomy. We both agreed that we wanted a reliable, long-term, preferably permanent, birth control solution. James felt that, since I had been the one to birth the babies, and since a vasectomy is an out-patient, in-office procedure, it made sense for our family. I agreed, and supported him.

Then, after looking more carefully at our schedule of benefits, James discovered that vasectomies are not covered by our insurance.

We stayed in limbo for the better part of a year, knowing that our insurance provider was going to change in a few months. We were hopeful that maybe the new plan would cover vasectomies.

Then Trump won the election, and everything health care related was thrown into uncertainty.

I had been resistant to considering an IUD (intrauterine device), mostly because the idea of having something inserted into my uterus kinda squicked me out. Ironic, considering my uterus has played host to two foreign entities for extended periods of time, but that’s how I felt.

However, with Trump awaiting inauguration and Paul Ryan heading up a rabid throng of anti-women Republicans, I felt that I no longer had the luxury of turning up my nose at an IUD just because the idea of it makes me uncomfortable.

I made an appointment with my gynecologist for early December and asked for information about IUDs.

I knew there were two kinds: the Mirena, which uses a low dose of hormones, and the Paragard, a copper, non-hormonal option. Based on my past experience with hormonal birth control pills, I was pretty sure I wanted the Paragard. My doctor agreed with me.

I have a great doctor. He explained the differences between the two, how they work, their effectiveness, how long they last, expected side effects, how it is inserted, how it is removed. We talked for probably 30 minutes. At the end of our conversation, I felt pretty comfortable with my decision to get the Paragard.

The one thing that worried me, though, was his description of the pain I could expect upon insertion. He compared it to labor: “Instead of having labor pains for hours, it’s like having labor pains for a minute.”

Having been through both an induced labor and an unmedicated labor, the prospect of enduring labor pains for even a minute was not exactly something I was looking forward to.

I went home, James and I discussed it some more, and I decided to go for it. I called my gynecologist’s office, they got preapproval from my insurance company, and I was instructed to call back when my period starts to schedule the insertion.

There are two reasons doctors like to insert IUDs during menstruation: 1. They can be sure you’re not pregnant. 2. The cervix is softer and more open at that time.

I ended up with an appointment the week before Christmas. Merry Christmas to me! I joke, but the timing was actually good, as I was off work, but both children still had school or day care. With the description of the pain I could expect, I was really not sure of how chipper I’d be the rest of that day.

I was not, however, able to schedule the procedure with my regular gynecologist. Instead, I was seeing the new female doctor in the practice for the first time. While I was thrilled to be seeing a female doctor (I had been skeptical of this practice’s three male doctors; turns out I love two out of three of them; not bad), I was not really happy with having the procedure done by someone I would be meeting for the first time that day.

The day came. The nurse who prepped me also compared the pain to labor. She spoke very familiarly about the procedure; it turns out she had recently had an IUD placed as well. But, she said, she has never had children, so she probably had more pain that I would.

I met the new doctor, and she immediately put me at ease. But again, she compared the pain to labor. I finally said, “Just because I’ve been through labor doesn’t mean I want to do it again.”

It turned out not to hurt much at all. Actually, I wouldn’t even call it pain, more discomfort.

The procedure has two parts: First, the doctor inserts a small rod to measure the depth of the uterus. If the uterus is shorter or longer than recommended, the device won’t sit correctly and might not work as advertised. Mine was the right depth. Yay!

Then the doctor inserts the IUD. The IUD is shaped like a T, and the arms are flexible. It is folded down into a straw, inserted, and then the straw is removed and the arms unfold, and the device settles into place.

No anesthetic is used, though it is recommended to take ibuprofen an hour before the procedure. No dilators are used to open the cervix. The entire procedure, from start to finish, took about 5 minutes. I had to remain lying down for another 5 minutes because “any manipulation of the cervix can lead to lightheadedness.” I did not experience that.

I had some cramping the rest of the day, but was able to control that with ibuprofen. After 48 hours, the cramping was gone.

I have to go back in a few weeks so the doctor can confirm that the IUD is staying in place and everything is as it should be. The greatest risk for expulsion is in the first month.

This has been a very bittersweet experience. I am angry that I was forced into choosing a form of contraception that I didn’t want because of which politicians were elected to office, but I am extraordinarily grateful that this option was available to me. I am angry at the double standard that forces the woman to assume the burden of birth control, and extraordinarily grateful that my husband shares that outrage. And, I am very relieved to know that my husband and I are able to decide for ourselves what the best options are for our family.

I am writing and sharing this to add a personal story to the political argument around health care and access to contraception. Our family is doing okay. We don’t have a ton of money, but we own a home in a great community, we have steady jobs, and our children are healthy and happy. All of that would be much harder, if not impossible, to maintain if we were not able to control the size of our family. We are excruciatingly aware of how easily the balance could be disrupted, and that many other families don’t have the stability we have.

This is why it is so important that our government protect our access to health care and birth control. The ACA actually helps real people of a wide variety of economic means. Planned Parenthood does so much more than offer abortions.

If you are in Connecticut, there will be a rally in support of Planned Parenthood at the State Capitol in Hartford on Wednesday, January 18, at 4:30 pm. Sign up here.

If you can’t attend, or you aren’t local, call your elected officials and urge them to defend Planned Parenthood.

And you can always make a donation. Planned Parenthood has pledged to keep its doors open even if it loses government funding, so it will need every penny we can collect.

Recent Comments